11. I’d been reading my copy of Swann’s Way for a while when one day...

The eleventh instalment of 'Oh, That More Such Flowers May Come Tomorrow' in which our hero remembers the desperate and unedifying adventures of his first love.

I’d been reading my copy of Swann’s Way for a while when one day I turned to the inside back cover and found these words scrawled halfway down…

Manifestation of sexual jealousy: rigorous examination of partner’s sexual intimacies (as imagined) … irrational suspicion – trivialities appear as ‘holy writ’ … infidelity in time (Proust).

The strange thing was that this was written in my own hand. I had no memory of doing so and no idea of how I’d come up with what wasn’t actually a bad little assessment, given that I hadn’t read it at the time. Seeing this again, after all those years, and after all that had happened to me since, I had the sense I’d written it as a message to my future self, somehow conscious that one day I would be looking for consolation within its pages. I also realised that I was, even at the time, writing about myself, and specifically about the year before I’d moved to Norwich, during which I’d been desperately in love with a girl called Maria, who lived in our little town, and who first broke my little heart.

Perhaps the strangest thing about Maria was that I’d dreamt her up long before I ever knew she existed. The equivalent of my ‘fisher girl from Balbec’ or ‘peasant girl from Méséglise’, I’d conjured her as a fantasy connected to the oak-lined hill that led from my grandmother’s house to the town centre (the first part of my route to school). Like the Narrator, and most other sixteen-year-old boys, this was a time when the idea of losing my virginity loomed large in my mind, and so I concocted an imaginary object of desire, upon whom these lascivious thoughts centred.

The fantasy ran as follows: I would first of all picture her walking ahead of me; after admiring her from a distance for a while, I’d centre my thoughts on her body, a fantasy within a fantasy; finally, she would turn her head, look my way, and stop. As I drew near, our pupils would lock, and we’d be drawn together under the influence of an inexplicable emotional gravity. She was beautiful, with short blonde hair and bright blue eyes. We’d smile at one another, then hold hands, then embrace like the eager teenagers we were. I’m pretty sure it was always raining. Finally, she’d take me to her house (conveniently devoid of parents), and lead me to her bedroom, where our passionate kisses would continue, etc. etc.

I played this scene out so often in my head that the smell of her imaginary skin and the taste of her imaginary mouth became almost real to me, although nothing like what I experienced when this adolescent pipe dream finally came true. It was just another ordinary day as I ambled down the hill, for once not engaged in this salacious routine, when up ahead, all-of-a-sudden, there she was, everything I’d pictured in my head, writ large in flesh and blood. Her name was Maria. She soon became my girlfriend. Within weeks, I was madly in love. Within months, all those things I’d fantasised about really did happen: the rain, the kiss, the house, the bedroom, the rest.

What I had no idea about at the time was the insidious caveat that comes appended to the satisfaction of sexual desire. It goes something like this: having had such intimacies granted, one becomes aware that they might be granted again, but this time to another. Nothing quite prepares you for this new, post-coital reality, which some ten months after that first time, unleashed its brutal truth upon me. A drunken party, another boy from another school. Maria extended those same intimacies to said boy. I found out. The world ended. Like Swann (who we’ll come to), I was ill equipped to deal with the cruel ontologies of jealousy. How could she?

After our relationship fell apart, I took to surreptitiously following Maria about (today we’d call it stalking), pining like a hungry dog for the hand that once fed it. I’d wait outside her house, staring up at her bedroom window in the hope of catching a glimpse of her; or I’d try to engineer ‘accidental’ meetings in the street, so that I could make the case for her taking me back. Worse still, fuelled by some perverse voyeuristic need, I’d track her and her new lover – a lanky, dark-eyed goth called Darren – at a safe distance and watch as they held hands, kissed one another, utterly broken by the sight of their happiness, but unable to turn away.

I tortured myself like this for months, eventually even attempting to ingratiate myself with him (conversations about The Cure) in order to get nearer to her. At night, alone in bed, I’d reel off scene after scene of self-concocted third-party pornography starring the girl I adored and this brazen interloper. It was only after I eventually left our little town, on my way to Norwich that autumn, that, thanks to the sanative effects of distance, I began to heal and realise that feelings like these were part and parcel of life, atavistic symptoms of the reptilian brain, which could be tempered by time, but were doubtless destined to return someday and ground my heart into dust once more.

My response to all this had been intense to the point of ridiculousness. Unable to eat or sleep, drinking myself into oblivion, I imagined that no one else in the history of humanity could have ever felt such pain, such abject misery, or had the same desperate and unedifying reactions as me to losing their lover. It was only when I read those strange notes that I’d made on the inside back cover of Swann’s Way years later, and only as I came to the end of the first volume, that I finally understood what they meant, finding a redemption of sorts for the foolish, fucked-up boy I’d been.

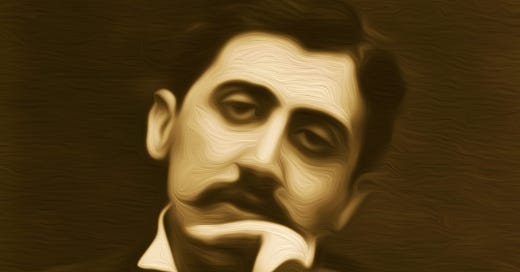

In the Search, this kind of sexual jealousy is picked over with such scalpel-like precision, that we must place its author alongside, and perhaps even above, the likes of Shakespeare, Euripides and Racine, as its greatest expositor. It brings us at last to Charles Swann, who is the kind of sophisticated, worldly figure the young Narrator can only dream of becoming. Rich, cultured and well connected, his is the large house the Narrator passes on his walks along the Méséglise Way, and who is also a regular dinner guest of his parents, the man visiting on that very first night described, who keeps his mother occupied late into the evening and thus plays a major part in denying him the goodnight kiss he so desperately craves.

Despite Swann’s ample credentials, he’s viewed by the boy’s family as provincial and bourgeois, merely the ‘son of a stockbroker’, when in fact he is welcomed in the highest circles of Parisian society, and a close friend of the Guermantes. This divergence of perspectives concerning the nature and circumstances of character is a trope that recurs throughout the novel, applicable to its entire cast, making it hard to pin down the truth of personality, which is exactly Proust’s point. Like everyone else, Swann is mutable, and we witness his transformations as the narrative proceeds and learn the story of how, as a younger man, he fell further and further under the spell of a former courtesan and archetypal belle du jour called Odette de Crecy, now his wife. We discover that as his love for her grew, he became ever more enslaved to her capricious ways, ever more deluded, desperate, and deranged in the face of her suspected betrayals. ‘I do feel that it’s really absurd that a man of his intelligence should let himself be made to suffer by a creature of that kind’ is the withering assessment of one of the many minor characters, Mme des Laumes, who pass through the story.

It’s an opinion that’s quickly castigated by the Narrator who describes it as an example of ‘the wisdom invariably shown by people who, not being in love themselves, feel that a clever man ought to be unhappy only about such persons as are worth his while; which is rather like being astonished that anyone should condescend to die of cholera at the bidding of so insignificant a creature as the comma bacillus.’

Need to catch up on previous instalments? You can find links to all the previous chapters here.