5. The weeks following that New Year’s Day were cold, dank and grey...

The fifth instalment of 'Oh, That More Such Flowers May Come Tomorrow' in which our hero goes to a party in south London.

The weeks following that New Year’s Day were cold, dank and grey, full of the kind of dismal days that plague southern England and northern France in equal measure, dredged up from the depths of the Channel, mist-filled, mysterious, and replete with an indeterminate longing…

Aside from my new-found appetite for Proust, I soon fell back into the familiar habit of solo drinking, breaking the resolution I’d only just made to myself. I was still desperately lonely and glad to receive an invitation to a Burns Night party a few weeks later. Perhaps some actual human company might also help take my mind off things.

Over the days that followed, this event began to take on a great significance in my mind, not only because of my fondness for literary flourishes, but also due to my long-held and entirely romantic fancy of being Scottish rather than English, along with the expectation of running into one particularly attractive woman from north of the border, whom I’d met some months before. In fact, I’d already concocted numerous fantasies in which we’d become amorously entangled, beginning with a Laphroaig-fuelled kiss in a darkened room, stretching out into marriage, children, and annual holidays to Tuscany with the in-laws.

And so, in late January, I found myself walking up to a large Edwardian house in south London, carrying two bottles of red wine and a concealed copy of Swann’s Way in my jacket pocket. The book now went everywhere with me, a hedge against insomnia for one thing; a secret weapon, guarding me against boredom or banality; an invisibility cloak I could throw over myself in case of social emergency.

Stretching out a frozen finger, I rang the bell, which echoed reassuringly from behind the door, and before I knew it, I was surrounded by warm, well-dressed bodies casually chatting away to one another; a witness to the repetitive action of mouths opening and closing, to tongues touching the backs of teeth, heads being tipped back in laughter, glasses being raised to lips, and meaningful and meaningless glances being thrown around the room. I’d been cloistered away for so long, I thought, as I moved among them, feeling something like an alien, that I didn’t know how to behave or what to say.

Thankfully, a drink was soon thrust into my hand, and eventually I found my voice, which I’d resolved to silence whenever the urge to talk about Proust made itself felt. This new relationship was not to be shared with anyone until I’d finished the book, for fear of somehow sabotaging my mission. It was special. It was mine. Proust, in the role of Philemon, was now party to my personal truth and private desolation in ways these people never would be. With them and everyone else, I would have to keep pretending.

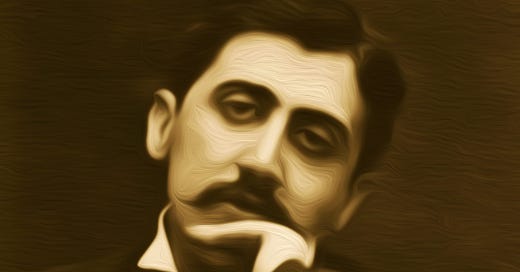

My new companion loved a bash, of course; his book being full of them. In early adulthood, Proust made it his mission to climb the exalted ladder that characterised French society during the Belle Époque. Such was his almost pathological fascination with the rarefied ranks of the French aristocracy, his desire to ascend, that even then he drew accusations of snobbery from those around him, with that trim moustache, awkward elegance, and importunate neediness.

An odd and somewhat voyeuristic presence, he was nevertheless charming, clever and well connected enough to be welcomed into the prim parlours and grand drawing rooms of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, that part of Paris where the nobility clustered together like so many gilded scarabs, idly eating asparagus and sipping champagne while watching their capital accumulate.

In retrospect, we know that all this party hopping was ultimately a part of some essential and almost unconscious programme of research. Without those ‘wasted’ years, his novel would never have existed. And so, we should certainly forgive him his early idolatry of the rich and famous, if that’s what it was. For the young Proust was no parvenu, more a man on an as-yet-undefined quest, with little idea of where his fascination would lead, drawn by the dismal and dazzling distractions of glamour, which he would eventually decipher and transmute into myth.

If further proof of his true character were required, there’s a marvellous anecdote in Edmund White’s short biography, which tells of one grandee who, soon after Proust’s death in 1922, found his butler desperately sobbing into a handkerchief: ‘But why are you grieving? Did you know Monsieur Proust?’ ‘Oh yes,’ the butler replied, ‘every time there would be a ball here, Monsieur Proust would come by the next day and quiz me about who had come, what they said, how they were related to one another and so on. Such a nice man – and he always left such a generous tip!’

Munificent to a fault and notoriously careless with money, Proust possessed a great and entirely organic empathy, which despite his idiosyncrasies, drew people of every social class toward him, like moths toward a curious and enchanting light. This was coupled with an unsurpassed eye for detail and ear for dialogue, an acute aesthetic sensibility, and a deeply sympathetic wisdom. With these tools, and his careful surveillance of the world around him, he would later pull off one of the most audacious literary endeavours ever attempted; something so great, it would eventually propel him into the pantheon occupied by the likes of Dante, Shakespeare and Dostoevsky.

But back to the party. I guess it was all so commonplace, especially when compared with the glittering gatherings peopled by Proust’s characters; the kind of affairs now enjoyed by the feckless offspring of global oligarchs. But even at this far more modest soirée, I felt self-conscious and somewhat out of place.

No matter how much my life had changed on the surface since leaving home at eighteen, I was still the same small boy from the same blue-collar town in the south of England that I’d always been (at least that’s what I told myself). In the intervening years, despite any tangible success or progress, I’d somehow become the sort of person invited to this sort of party, where the children of the middle classes drank craft ale and talked casually about the kind of life I’d never have.

The thing was, no matter how much I pleaded my plebeian provenance, my peers never believed me. Because I looked and sounded just like them. What they failed to understand was that my reality, although outwardly similar, was absent the capital on which theirs rested. There was no stock portfolio, pension plan, house in the country, or parental inheritance to call upon. The only reason I’d made their acquaintance in the first place was because I was part of that last generation for whom university was subsidised by the state. I went because I had nothing else to do.

Since then, I’d been suffering from the gradual accrual of debt and anxiety, both products of the fear of being left out, but also of boredom and blithe acquiescence. This inadvertent stumble up the social ladder had bent my world out of shape, making it prey to a background radiation of envy and indignation, by the perpetual feeling that something wasn’t quite right.

As I looked around the room at the doctors and lawyers, actuaries and accountants, arts professionals and ‘creatives’, who were now my friends, the frequent and familiar sense of my own fraudulence grew out of all proportion in my mind. Weren’t we all suffering from a version of what Nietzsche dubbed ‘last man’ syndrome? Creatures bound by the tyranny of comfort, transformed into timid mouse-men, seeking nothing but security and distraction? Wasn’t this party and all the others like it, and so many of the things I occupied myself with, just dull insulation against my ability to engage with what life really was: a battleground of Schopenhauerian will, a crucible of endless suffering, a slaughterhouse?

And so, as my mouth opened and closed, spilling out cheap words and even cheaper witticisms, as my eyes pivoted this way at that, as I drank more craft ale, and as the beautiful Scottish woman sidled off with another, more self-assured, solvent, and sexier man, I began to realise that I’d forgotten something deeply important; something sacred that had no connection to the conventions of the social realm; something known only by that young boy who used to be me, book in hand, prone amid the flowers in his grandmother’s garden, or beneath the Christmas tree in the middle room, quietly listening to the faint incantations issuing from the fireplace.

And it was at this precise moment, caught between all these well-nourished bodies, but utterly alone, that I knew only by meeting this boy again, only by following him into the rabbit hole of our secret history, might I understand what it was. The only difference was that now I knew where to find him. For it hadn’t taken me long to suspect that my own past would be waiting for me within Proust’s novel, and that if my new friend possessed any kind of power, it would be found in what it meant to submit to his work at the expense of fitting in.