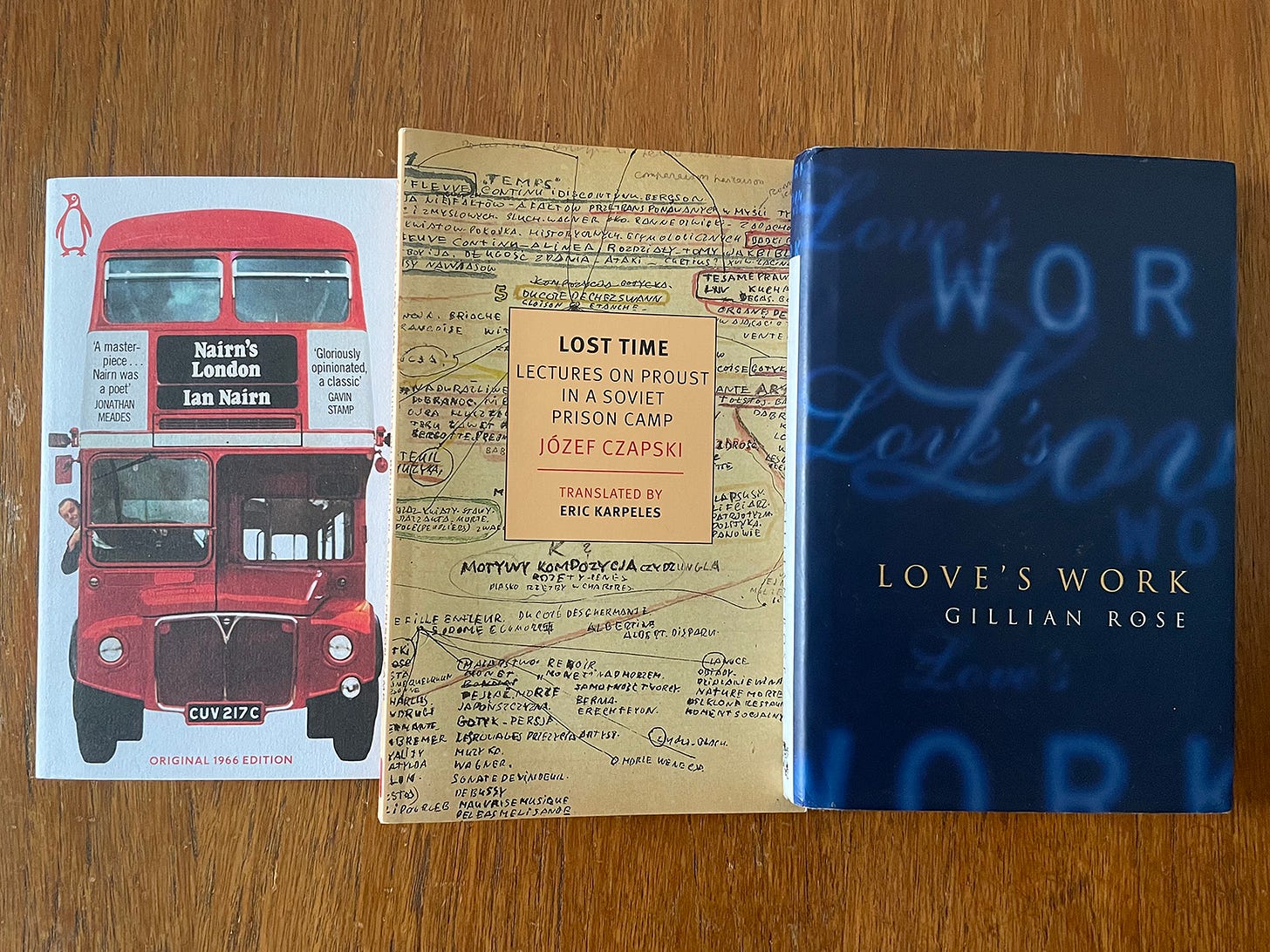

Three short books to treasure

A selection of three short non-fiction books that have inspired me over the years. Each one is worth searching out and adding to your own reading list, or would make a great Christmas gift.

Hello everyone! Happy Christmas! I just wanted to share three short books that are very special to me. They each offer new ways of seeing, which is what a good book should do. And they each bear repeated reading, providing something to which we can return, but which always feels like a new beginning. I hope this might inspire you to seek them out and discover their magic for yourselves, or give a gift to a loved one.

Speaking of gifts, there’s 50% off a subscription to this newsletter for the next six weeks. Just click on the button below. All readers will be getting an exclusive Christmas-themed short story, which I’ll be posting next week.

1. Nairn’s London, Ian Nairn, Penguin, 1966

This wonderful guide is described simply as ‘the author’s personal list of the best things in London’. If that was all it was, then it might not be worth mentioning. But the author is Ian Nairn, almost certainly one of the greatest writers on architecture and the built environment to ever grace the shores of old Albion.

Roaming across the metropolis, Nairn brings his keen eye, fierce intelligence, and innate empathy to bear on the landmarks, both famous and obscure, that make London one of the world’s great cities. His precise, evocative prose will make the resident quietly proud, the ex-pat homesick, and the prospective visitor rush to book a ticket.

There is something remarkably human about the way Nairn writes, and I think that’s because he understands intuitively the essential humanity of buildings, and where architecture goes right and goes wrong. Buildings reflect the people that make them: their beneficence, their imagination, their hubris, their cupidity. They also reflect (or should) the people for whom they are built. And that’s what we get here: a wonderfully human whistle-stop tour of the city, from Uxbridge to Dagenham, written in such a way that reveals the detail of its individual parts, set amid the majesty of its whole.

Throughout, Nairn’s passion for his subject shines through. Buildings aren’t a matter of life and death; they’re far more important than that. They’re what we leave behind, for the children of posterity to live, work and play in. They are both the ancient mud-huts that protected us from the elements and also the great Gothic cathedrals that connected us to the divine. In an act of unwitting reciprocity, they come to define us, almost as much as we define them.

Nairn is a true poet of place, whose writing often outdoes the very thing it’s describing. Here’s a line about the Chelsea riverside: ‘The time to see it is in the afternoon with a warm front coming in, and the sun like a blob of melted butter shining down on the oily, sullen river.’ I could (and often do) carry this book with me whenever I’m in London; a reminder of the audacious beauty of the city, but also of the kind of wit and wisdom that is required to appreciate and document it.

2. Lost Time: Lectures on Proust in a Soviet Prison Camp, Józef Czapski, NYRB Classics, 2018

This short book represents a remarkable feat of recollection under the most difficult of circumstances. In 1940, Józef Czapski was interned in a Soviet prisoner of war camp, along with many fellow officers from the Polish army. Desperate to keep their minds occupied and spirits together, the men held secret lectures about topics close to their hearts. Czapski, who’d been in Paris during the 1920s, where he’d first discovered and devoured Proust, decided to relay the story, themes and implications of the maestro’s great novel, all from memory.

Luckily for us, the lectures were transcribed by two of Csapski’s fellow inmates. The text is a testament to the power of literature, and to the enduring importance of what we call the ‘humanities’. Subject to the daily degradations of prison life, these men cleaved to one of the things that make us human: our art.

And Proust, it seems, was of particular relevance. For Proust is the great writer of lost and wasted time, which makes him the perfect subject for those serving it. If À la recherche du temps perdu teaches us anything, it is how to process and then transform the time we have lost or frittered away. Building on Bergsonian foundations, Proust attempts to tap into and render the continuous flow of life, which cannot be grasped by intelligence alone, but by intuition, imagination, and instinct.

Csapski is alive to this idea and finds a neat way to describe what Proust was trying to get at: ‘It’s not what the stream is carrying along with it – branches, a corpse, some pearls – that represents the particular direction of the stream, but the current itself, continuous and without end.’ He goes on to describe the sinuous beauty of Proust’s sentences, the web of allusions and associations they contain, and their ability to unlock ‘the secret laws that govern facts… the least discernible secret workings of being.’ His central thesis is simple: that in its attempt to distil the rich tapestry of life, this great novel has something to say to us, something that makes itself apparent through the sustained act of immersion it requires of its reader.

For lovers of Proust, this book is a must. They will lap it up. For those less familiar with the subject, it provides a concise and compelling primer, a reason to consider embarking on the long journey it describes. But perhaps more than both those things, it affirms what art might do for us in the face of tyranny, corruption and chaos; how it might lift us up above those things, and keep our eyes bent towards the light.

3. Love’s Work, Gillian Rose, Chatto & Windus, 1995

This is one of those books I return to regularly. Dense in parts, it can easily take multiple readings. In fact, it demands them. We meet some of the important figures in Rose’s life. We hear about their lives, their deaths, and their influence on her own ways of knowing. We also get something of an origins story – of how Rose found her way toward language, literature, and philosophy, and what she then did with it.

There was a successful academic career, of course. And here we’re given a distillation of her thought, which, put very simply, offers a considered and compelling critique of postmodernism relativism. She also draws out the connection between philosophical practice on the one hand and human relationships on the other, describing an existential condition of sadness that is as hardwired into us as breathing. It’s out of this sadness, she argues, that philosophy itself was born, rather than out of any totalising need to establish an absolute system of knowledge, law and governance.

Her analysis places the humanity back into the discourse, countering the tendency to abstract it away. Truly meaningful thinking involves a confrontation with the fact of this mutual sadness; a reckoning with the rational and the irrational. If we look hard enough, we might find love and respect for those that share the burden of Being. Only then can we begin to get a measure of our ontology in relation to ‘the other’. At the heart of our most intimate relationships resides a sense of irresolution, and it’s with this that we must contend as we move through the world: what she call’s ‘love’s work’.

For Rose, this work involves a confrontation with our own limitations. To be alive is to be incomplete; to recognise this in oneself and one’s lover is to reckon with our ethical duty toward one another; it is to unearth the compassion from our condition of sadness. The book ends with a bold declaration, a message of hope and courage to us all: ‘I will stay in the fray, in the revel of ideas and risk; learning, falling, wooing, grieving, trusting, working, reposing – in this sin of language and lips.’