41. Heading east, I crossed Madison Avenue...

The forty-first instalment of 'Oh, That More Such Flowers May Come Tomorrow' in which our hero finds a strange sort of solace in Washington Square Park.

Welcome to 'Oh, That More Such Flowers May Come Tomorrow', a novel I’ve published as a serial. If you’re new here, you can start at the beginning, or use the links below to navigate to other chapters.

<Previous Chapter | Contents | Next Chapter>

Heading east, I crossed Madison Avenue, Park Avenue and Lexington, then turned right onto Third Avenue, to make my way south through the Upper East Side…

Above the Chrysler Building, I could see dim patches of blue and the flat, wisp-like disc of the sun straining to penetrate the mostly grey mantle that still cocooned the city. He looked younger, I thought. He looked stronger. The face in the gallery had a sort of ruddy glow. I was sure of it. But can ghosts look healthy? That seemed absurd, and yet didn’t everything.

With that, I dashed across the street into Starbucks to get a coffee and to ground myself in its reassuring banality. It didn’t work, so I pressed on, struggling through the madness of Midtown. I eventually found myself in the East Village, where quite coincidently, I ran into Alistair, whose bright eyes brought a smile to my face, so glad was I to see someone familiar, to speak on sympathetic terms, to feel normal for a moment. He asked if I wanted eat. Minutes later, we were ensconced in one of his (and apparently, my father’s) favourite spots for lunch. I noticed it had the same name as his cat, which – it dawned on me – had clearly been named after it. Veselka.

After the disconcerting events of the morning, I was relieved to have company, happy for the social gears of my brain to be called back into action. For a while we talked about everyday things; about living in London, about the pubs, the food, the culture; about my job, and what I wanted to do with my life. I reluctantly confessed my wish to be a writer, which Alistair seemed to accept at face value, as if it was an entirely plausible ambition. And so, we talked about books, and especially about Fitzgerald, whom he loved as much as me. I told him about Professor Summers, about the lecture he gave all those years ago; how it blew a hundred tiny minds wide open; how my world had never been quite the same since.

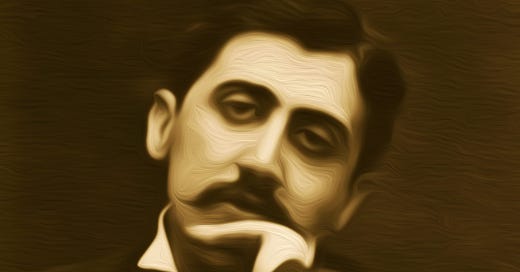

It was at least a full five minutes before I mentioned Proust. I tried to explain what reading the novel had been like, but couldn’t find the words. I tried to convey the thinking behind my decision; how I’d hoped the immersion in such a substantial, all-consuming, all-conquering work would allow me to take myself out of the painful reality I’d been living through, and how, having done so, I’d begun to see things in a new light. Again, I failed. You mean things are better now, he asked? No, I didn’t mean that at all. Things were… just… different. If anything, I told him, the world had become an even more complicated place. Certain realities had been exposed. I’d realised that grief never really goes away; I’d realised that suffering was the stuff of existence; I’d realised that the dead cleave to the living and the living to the dead; and I’d realised how unjust and unfair everything was. Finally, I said, I’d realised, despite all this, how achingly wondrous it was to live and love and to follow the line and language of art, whichever way it went. He smiled. I paused. Eventually, I asked him if any of this made any sense. It does, he said, completely.

The second silence that followed was comfortable. We’d both become caught up in the net of our own thoughts. Minutes later, staring at, but beyond each other, we realised this at exactly the same moment and burst out laughing. It was only at that point, with the laughter lingering in the air, that I felt able to ask about what had happened to my father toward the end of his time in New York, about why he’d left. Alistair hesitated; he wasn’t really sure. It all happened so quickly. He told me that he’d steadily become angrier at the world. Angrier at everything. As if he’d lost the ability to believe in the illusion that keeps everything patched together. At the same time, he appeared to have lost faith in himself. For a man like him, who’d always relied on his natural charm, his wits, his intuition, this must have been difficult to fathom. To compensate for the loss, his drinking spiralled out of control. Alcohol became the answer to all questions. And New York obliged. He was drunk more often than not. And if he wasn’t yet drunk, then he’d soon be on his way, topping up his morning coffee with bourbon, slouching around dive bars in the daytime, playing pool with the punters, ducking out for joints, ducking back in for even stronger substances. His reliable habit, a friend for so many years, had finally betrayed him. He lost the job at the gallery. Anything that stood in the way of the next drink became a problem; anyone who did the same was subject to reproach. Being around this became difficult and so people drifted away. Some called him ‘the crazy Brit’. Alistair stuck around but felt powerless to do anything. They argued. Long battles full of rage and recrimination. Their world got darker and darker. Then one day, Alistair found a note on the kitchen table. He was gone.

By the time we left the restaurant, the last of the snow had stopped falling, and the sun was breaking through several large rifts in the cloud. The wine we’d had with lunch had taken the edge off things, making me feel somewhat calmer. Suddenly, New York seemed a much more hospitable place than it had earlier that morning. Alistair and I hugged a goodbye, my arms hardly reaching around his great, bear-like frame. I couldn’t bring myself to tell him about what I’d seen; and in the few hours we’d been sat talking and eating and drinking, I’d again rationalised the phantom away as either temporary insanity or just someone with a similar face. Yet at the same time, I knew that I was going to keep wandering the streets for the rest of the day and for the days and weeks that followed if necessary, to find again whatever it was that I’d witnessed. I knew that my rationalisations were just that, part of the narrow realism to which the human brain, fearful of the unknown, held fast, and that the universe could easily cook up a ghost or two if it so pleased.

I walked south again; and then west, crossing Bowery. I soon found myself on Bleecker Street, a name I recognised from my father’s letters. I closed my eyes to the cold and tried to imagine what it must be like in the summer, in the dog days of August; to picture myself living somewhere like this, in a small apartment right in the heart of this strange and incredible city, of existing in the middle of the relentless energy that surges through it, of contending each day with its magnificence and terror. The thought made me spin. Would I thrive? Would I drown? Either way, I was soon lost in daydreams of new adventures and amorous intrigues among the latticed streets of the Village, which in my head was forever fixed in the late Seventies: crime wave, heat wave, new wave. Surely, New York (not London) was the only place to be to truly obliterate the past; to cleanse myself of the sickness that had afflicted me for so many years that I’d forgotten what it felt like to feel truly happy. Forget London. Forget everywhere else. Why not just stay here forever?

But wasn’t this all just another delusion? What was my father’s ghost if not the past writ large? If my journey into the Proustian universe had taught me anything then it was that exorcising the past was neither possible nor desirable. That the past was a living and fluid thing, always at work within us – something made clear during the novel’s final party, at the moment when the Narrator hears again the ring of a bell on the garden gate of the house at Combray; a noise which always signalled Swann’s departure and thus the arrival of his mother to wish him goodnight:

‘Yes, unmistakably I heard these very sounds, situated though they were in the remote past. And as I cast my mind over all the events which were ranged in an unbroken series between the moment of my childhood when I had first heard its sound and the Guermantes party, I was terrified to think that it was indeed this same bell which rang within me and that nothing I could do would alter its jangling notes.’

Ultimately, it was this conception of time, what he calls ‘Time embodied’, that the Narrator comes to see as the future basis of his work. And it was to this idea, the idea of work, that my own mind took a turn as I walked the frozen streets of New York. For I knew that this was where my father had foundered and where I must try to succeed, to make something worthwhile out of all this indulgent agony. Not for anyone but myself, or for any grand purpose but my own; simply for the sanative alchemy of it, which would be consolation if nothing else. With work came meaning, or at least the suggestion or possibility of meaning, and that was all anyone could really hope for.

I turned up Thompson Street and headed north into Washington Square Park. The snow was still thick across the ground and luminous with the reflected sunlight. The intense glare made me tighten my eyes. Everything had resolved to a stark and abundant whiteness. Still a little drunk and disoriented, I sat down on a bench, warmed by wine and the winter sun, which felt incongruous, like the world out there and the world inside had been separated, and that I was somehow a part of one while looking out over the other, not entirely sure which was real, or which had primacy.

In the distance I could see the thin dark shapes of people moving across the park, like something out of a Lowry painting, while others, static, solitary, sat on benches like me. I didn’t feel isolated or lonely, which was how it usually went in such moments; it felt like there may be others with me, like we were all one and the same, part of some deeper reality. I looked up into the sky, which seemed at once everything and nothing. I drifted away again. It was only after I moved my head down and looked straight ahead that I saw – this time I was sure of it – my father’s young and vigorous face, younger than my own, sat opposite, just a short distance away from me.

This was the face I remember stooping down to kiss me goodnight; the face that was an assurance against injustice and cruelty; that signalled salvation from the eldritch darkness of infancy; its deep blue eyes burning with the same world-swallowing love that I remember as a boy. This was him, I was sure. As real and seemingly human as anything real and seemingly human could be. The suggestion of blood and muscle beneath the sheen of skin; of form and flesh. A face and a body smack bang in the middle of this all-too bizarre American reality.

And so, there we sat, for what seemed like an eternity, holding one another’s gaze; and I can remember thinking how, in that moment, it was as if I could sense the strange and imperceptible movement of mute particles all around me – flowing, merging, reverberating – some turning themselves into lampposts or trash cans or trees, others into the very thought that makes the apprehension of lampposts or trash cans or trees possible; what we typically call consciousness; no more and no less miraculous than photosynthesis, parthenogenesis, or bioluminescence. And if we’re anything at all, I thought, then we’re simply the universe’s accidental practitioners, unwitting vessels burdened with the weight of a terrible and holy magic – a yardstick by which the void measures itself. I wondered too if this was death pressing itself up close to the mortal world, making itself known for reasons beyond my comprehension, playfully mocking the laws of time and space; death in the form of love regained, death making its latest claim on my brief life. For in seeing him like that, and thinking of myself, of him, our faces so similar as to be almost one and the same, I realised that while he was certainly dead, I was, still fool enough to think myself a wholly living thing and not, which was closer to the truth, something half-dead already.

There I remained, peaceful at last, seemingly free of time’s tyranny; and in those minutes or hours or however long it was, everything that had happened to me, all the pain and turmoil and anguish, became like once immovable rocks now ground into sand. It was only when I felt physical reality reassert itself in the form of fluid flowing from my eyes, warm against my cold cheeks, salted like the sea, that I understood (as with the Narrator and his grandmother) that my father had, after years of confusion and disbelief, finally been returned to me, not as the sickly shadow he became in later life, but as the compelling, charismatic, learned and loving man he once was; just as I also realised that he was truly, truly dead, and that I would never have him or hear him or hold him again.

And in that moment, I was glad of the tears, which broke over me like waves, washing away the unspoken terror that had come to define my existence. Breathless, I brought my hands to my face and rubbed my eyes with the sleeve of my jacket. As I did so, everything went dark, and when I looked again at the world seconds later, across to the place where he’d be sitting, he was gone again, back to wherever it is that the dead dwell. Gazing around the park, everything was as it had been. The lampposts were still lampposts. The trash cans were still trash cans. The trees were still trees. The snow still covered everything.

Need to catch up on previous instalments? You can find links to all the previous chapters here.

Phew. What is there to say? Are you ok now? There is always a word that catches me. This time it was eldritch

Mighty prose Ben and a mighty interior life. I'd like to hear more about that lecture on, was it Fitzgerald generally or Gatsby in particular?